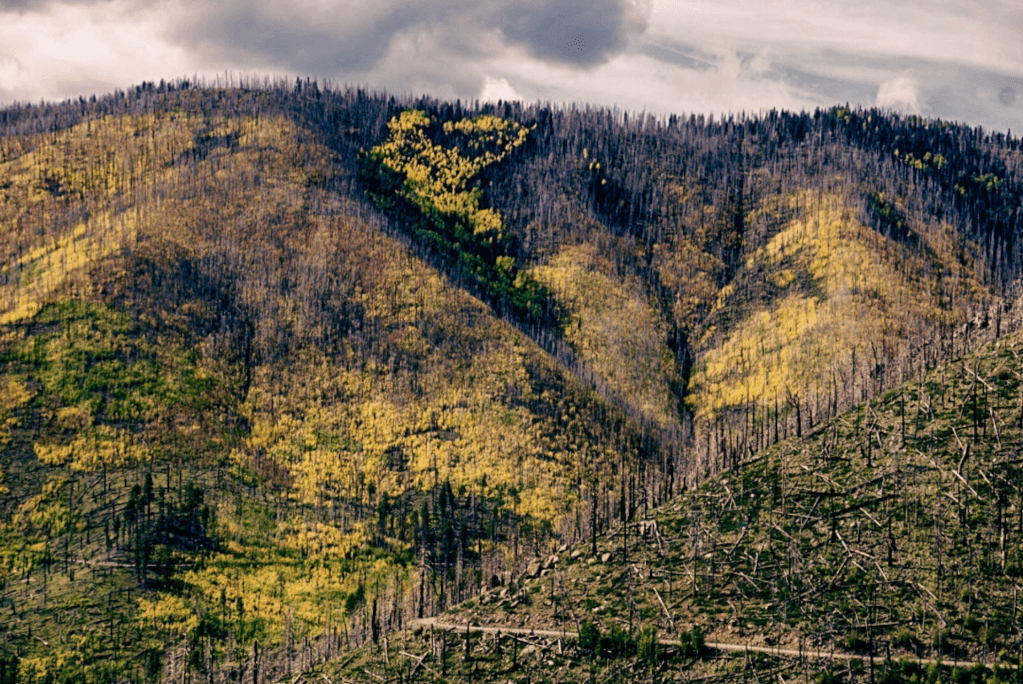

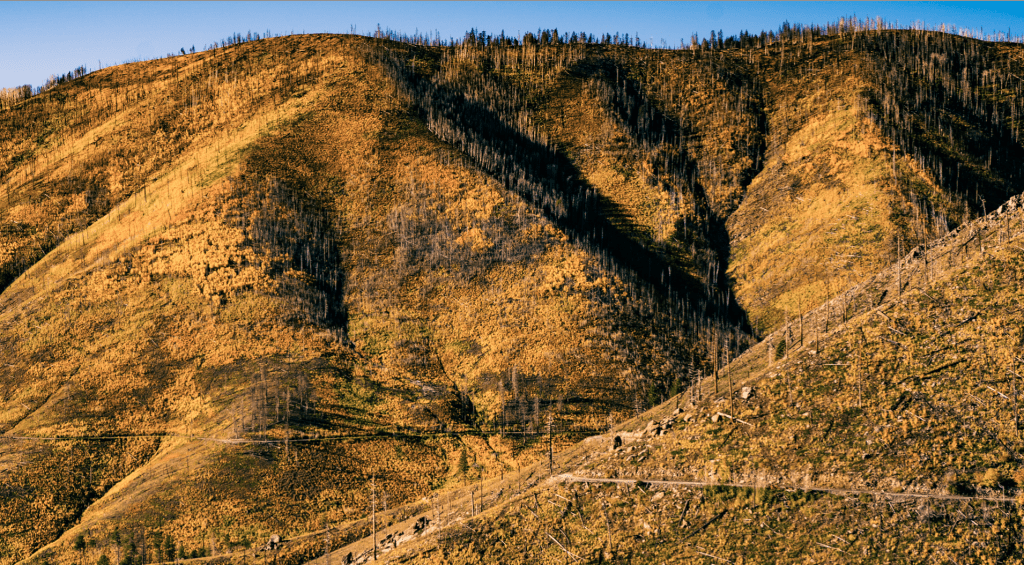

~ When I think of setbacks, I always think of Waterline Road in Flagstaff, AZ. In 2010 a huge fire destroyed all the trees on this road. The top picture is from 2018, when a grove of aspens emerged shaped like a heart. We called it, “the heart of the mountain.” However, in 2022 the mountain burned again. The second picture is the same view shot in the fall of 2022. One might say that the heart of the mountain is gone, but I prefer to view it as having exploded over the whole mountain. I’d say that the gold hills in the second photo support my claim. Read on about choosing meaning toward your circumstances 🙂

Mimi, thank you for your question. So many can relate. Although each person is surely different as to the specifics of their personal struggle with injuries and setbacks, I suspect that these struggles stem from some similar origins.

In order to understand these origins, I like to reference a personal story:

The Mountain and the Weather

In Flagstaff, Arizona, there is one mountain range, the San Francisco peaks. At 12,000 feet, Mt Humphreys is the tallest of the peaks, and usually provides a grand, yet softly refined presence over the town.

One day, I was walking North on the NAU campus. Mt Humphreys, clear and beautiful, commanded the skyline. That day, I also felt clear and beautiful, content and purposeful and grateful for my life. As I looked up at the mountain it occurred to me that how I felt in that moment was like the mountain on a clear day. Nothing uncomfortable clouded my perception of myself and my life. I had a strong sense of belonging and I both knew and felt that I had an irreplaceable role in that place in that moment.

It came to me then, that to see this way, is to see both myself and the mountain most accurately. I say this because I could see my own capability and my own possibility, as well as areas that I could still benefit from growth. But, my qualities out-weighed my weaknesses instead of the other way around.

The weather in Flagstaff is predominantly sunny. However, storms do roll in, and when they do the mountain can be completely obscured. The clouds can be so dense in fact that Mt. Humphreys disappears completely. If someone were to arrive in Flag on a stormy day it would be easy to presume that there are no mountains near Flagstaff.

In our human lives our own illusions of un-belonging and inadequacy can roll in just as thick. Some days our true self is nowhere to be seen. It can be easy to doubt that person exists and easy to forget the way that person views themselves or the world.

When we are blinded by weather it helps to look upon ourselves the same way that those in Flagstaff look at the void when Mt. Humphreys is invisible:

No matter the storm, the mountain is there. Even when we can’t see it we choose to believe it is there, because we know that it is for a fact. That mountain, grand yet refined, there is only one like it. It is absolutely real whether it is obscured by cloud, or clear as day across blue skies. The mountain on a clear day, that’s who you are. Anything else is just weather.

You are probably already guessing that the downward spiral that you referenced in your question is a form of weather. The first way to work with weather is to understand it, so lets explore why injuries and setbacks are often so stormy.

In my opinion, most human weather arises from 3 primary storm cells and one cultural misunderstanding:

Primary storm cells

Need for belonging/ fear of exclusion

Need for certainty/ fear of the unknown

Need for meaning/ fear of purposelessness

Cultural misunderstanding

Attachment to linear progress

Here is a brief summary of each and how they relate to injuries and setbacks:

Need for Belonging/ Fear of Exclusion

Humans have a deep need for connection. Many of you reading this are likely aware of the physical and psychological benefits/ necessity of regular positive relationships. Sometimes, depending on the setback, athletes and artists are unable to be present in environments where their regular positive connection is readily available. Greater isolation alone can negatively impact well-being.

However, it is not just isolation that gives rise to weather. Us humans are also very sensitive to our status within a community. The explanation for this reaches back to primitive days when human beings were living in interdependent tribes. Those of high status were the safest in their community: they received the best resources, mates and protection. Back then, status was a survival factor, and threats to status were threats to survival.

In modern day, status is determined by factors of value to your community. For example, if you are a runner, how many miles are you running each week? What are your personal best times? If you are an artist, what skills have you mastered? What new work are you producing? When factors that are granted status within you community are in jeopardy, perhaps due to illness or injury, your stress system is likely to become alarmed. An alarmed stress system sounds in different ways for different people at different times. Sometimes we feel anxious and worried, other times depressed and dejected. But, regardless of how your stress system responds to a perceived threat to your status in your community, and regardless of how uncomfortable it is, know that your reaction is natural.

Need for certainty/ fear of the unknown

One of the primary functions of the human brain is to attempt to be certain about what is coming in the future. When we are certain we can be prepared. When we are prepared we can take steps to make sure that we are safe.

One of the most difficult elements of injuries and setbacks is their often unknown duration. When faced with an indefinite unknown in an area of our life that provides connection, status and meaning our nervous system easily becomes distressed. The most common mental response to these unknowns is to predict the worst-case scenarios. This response s called the negativity bias. The negativity bias is a cognitive coping mechanism which narrows our attention to all possible threats in this meaningful unknown in our lives and excludes all possible positive unfoldings.

Similar to our vigilance about our status, the negativity bias has a helpful intention: to prepare you to expect the worst just in case it happens. However, the negativity bias is often extremely inaccurate and causes a person to suffer fear stories about their future that never come to be.

Need for meaning/ fear of purposelessness

This third primary storm cell, our need for meaning, is one that I have only just recently included in my theorizing. This one is related to your experience of “identity crisis” when injured. We are deeply meaning-seeking beings who will invest ourselves joyfully and exhaustively in things that matter to us. We are also vulnerable to despair when our lives “lose” a source of meaning.

Most of us unconsciously associate what we do with who we are. I am a dancer; I am an athlete. This association is understandable, given that our chosen crafts are often our primary gateway through which to express who we are. When we can no longer participate in our meaningful activities our gateways to self- expression, and opportunities for purposeful action appear closed.

Attachment to linear progress

The first three storm cells that I just outlined are natural drives which we inherit as humans. This last source of weather, our attachment to linear progress, has been taught to us by our western society.

Who in the western world does not perceive pressure to be constantly improving? Especially in areas of our lives valued by our community. When we reflect back, most of us can see how linear progress in school, professions, sports, and relationships is viewed as “good” and expected. Throughout our lives, deviations from linear progress are met with displeasure, nervousness, and often guilt and shame.

I wish that it was more commonly known that most (perhaps all) wisdom cultures and traditions ascribe to a different model of “progression.” These people live by a narrative which sees growth as cyclical, seasonal and dependent on power outside of our own. “Achievement” is the development of greater compassion, patience and humility. This model of cyclical progress is far more in line with how life actually goes. If it was a more prominent feature of our society I suspect that our “setbacks” would be viewed very differently. Perhaps we would not see them as setbacks at all.

So, injured athlete or artist, what are you supposed to do with all of this? The first thing to do is to recognize that your struggle is natural. It is not your fault. As a human being threaded with the storm cells listed above, experiencing weather during setbacks is natural.

I have many methods to work with this particular weather, but here is a favorite:

I have borrowed this method from the famous, Viktor Frankl. Psychologist and holocaust survivor, Frankl developed a method of therapy centered primarily around the human need for meaning. Here is a quote which summarizes his core beliefs:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Frankl developed a method for working with difficult circumstances which he called the creative method. This method involves asking oneself 3 questions. Here are the questions as well as some suggestions for how to answer them that addresses the storm cells listed earlier:

- What can I give to the current circumstance?

Perhaps you can attend training or practice and cheer others on (this attends to your need for meaning and belonging)

- What can I allow the current circumstance to give me?

Perhaps you can us the time that you are sidelined to watch and learn? (this attends to your need for meaning, belonging, and you take control of your learning which creates a known opportunity within the unknown)

- What is my attitudinal stance on what is happening? What meaning am I going to give to my circumstances?

Considered carefully, you could include all of the above in your answer. Perhaps this is an opportunity to support your fellow artists (belonging and meaning), learn from a different perspective (some control in the unknown), and therefore improve (linear progress).

Or, perhaps this is an opportunity get to know your own human weather, learn about its origins (a good therapist can help here) and to grow wiser about oneself and one’s world.

On this subject, Frankl writes: “Ultimately, a person should not ask what the meaning of their life is, but rather must recognize that it is they who are being asked.”

I wish you meaningful growth and healing.

Leave a comment