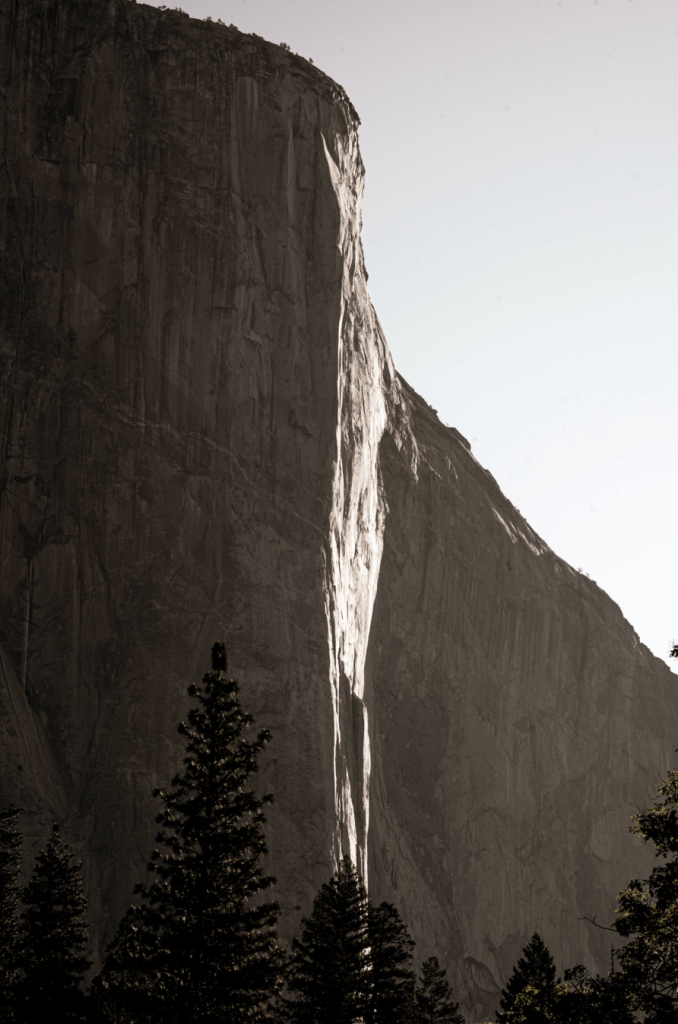

~ MYLES, EAST COAST

~ This is The Dawn Wall in Yosemite National Park. For many climbers this is their “sub-14:40.”

Dear Myles,

I am answering your question sitting in the NAU tent at the Big Sky Conference Championships. So, wise advice from true experts on this topic is readily at hand! I will share the thoughts of some of these experienced athletes intertwined with my own as we go.

To me, this question has a few key layers:

You are the slowest seed in this race by a fair bit.

You are “swinging for the fences,” so to speak. You are taking a leap of faith that you are fit enough to make a big jump in ability-wise at this distance.

You feel like you are expected to make that jump.

You are afraid that you won’t reach your goal.

Let’s address each of these one-by-one:

You are the slowest seed by a fair bit.

This means that you might actually be the slowest in the race, or you might not. Your coach will be the best source of advice as to strategy and position, etc. But, my NAU friends had some comments about this:

Colin Sahlman recommends: “get in the back of the pack and hold on – and know that you can!” This mirrors the approach that I have seen the NAU athletes take in races that might be on the quick side for them.

David Mullarkey shared, “I was in that position last year! My 3k PR was 7:58, but I was entered in a race that was being paced at 7:40. Get in the back and expect it to hurt early. But, trust that a few of those guys are going to run slower than their seed. Someone will come back to you. That’s what happened to me and as they did, I gained momentum.”

And, yes, David did achieve his goal.

Caleb Easton responded from a different angle: “how would you race if you didn’t see the heat sheet?” he asked.

You are “swinging for the fences.” You are taking a leap of faith that you are fit enough to make a big jump at this distance.

As David Mullarkey referred to earlier, an effort that might be right at the edge of your capabilities means that the pace might feel uncomfortable early. I would advise you to plan in advance to break the effort into chunks. Once you are in position, focus on what you need to do to compete with the people around you one chunk at a time. Try your best to tell yourself that competing inside each chunk of the race is your only task for that day. This will help you cope with the discomfort.

Regarding determining the size of each chunk, ask yourself, what size chunk would feel doable even if I am hurting? For example, you might divide the race into 12.5 x 400m, or you might view the first mile as 1 chunk, then divide the middle mile into 4 x 400m, then the last mile into 8 x 200m. The chunks should be larger in the part of the race where the effort is easier and smaller in the parts where it is likely to be harder. Check in with your intuition as to what size chunks feel right for you.

Ignore the clock as best you can. Keep your attention on competing with the people around you. A focus on competing will help you stay engaged in the race no matter how fast you are running and will protect you from the emotional fluctuations that can arise from looking at, and potentially reacting to, splits.

An outcome goal like running a big PR can be very captivating, distracting and stressful if you focus on it too much. You will give yourself the best chance of running fast if you can let go of your thoughts about time and instead focus on the task before you.

You feel like you are expected to make that jump.

Expectations are one way that our mind attempts to create a false sense of control and certainty regarding scenarios that matter to us. I suspect that they might be the most common inhibiting mental factor that runners experience.

Expectations sound like “I should be able to do ____________ because of ______________ workout.” Or, “coach says that I should be able to break 14:40 because ________________.” Or simply, “everyone expects me to do _____________,” which is less an attempt at certainty and more a threatening notion that is not necessarily true (more on that in a moment).

When the mind attempts to create certainty regarding an outcome that is currently unknown, the body and nervous system become alarmed. Deep down you know that your control is limited. To suggest that you should be able to be certain something that you only have partial control over stresses out your deeper intuitions.

Expectations also establish a bar that can set you up for disappointment. A clear way to “fail” is introduced into an opportunity where a notion of failure is not necessary. Racing does not need to be about succeeding or failing. Racing can instead be viewed through the lens of lets see what I can do! We don’t know if you are capable of running 14:40 on that day in that race. You might give the best effort that you have on that day and there still might be a headwind, or the race might be slower than you hoped. You might commit to the middle of the race like you never have before, or take your bravest risk yet, and still run 14:51 (or something like that) – a huge improvement in execution and outcome and a success in so many ways! But, if your expectations were stuck on 14:40 you might feel still feel like you failed. How unfair to you – someone so brave and hard-working.

In my work I try to help athletes notice and release expectations. One way to do this is to transform them into hopes. I hope that you can break 14:40! I suspect that others do also, and its possible that you are mistaking their hopes for expectations.

At NAU we intentionally meet races with a sense of curiosity. For example, in this 5k, how relaxed can I stay in the first mile? Can I maintain my position to the 2-mile mark? How many people can I pass in the last 800m? I wonder how fast I can run today! The curious lens releases notions of expectation and greatly reduces the sense of potential failure regarding the outcome of the race. As a result, curiosity enables greater calmness, enabling the athlete to stay present and focused, which calms the nervous system, and helps the body feel safe and willing to give its best.

You are afraid that he won’t meet expectations.

When an athlete is afraid that they won’t meet a goal they are usually also afraid that not meeting the goal means something negative about them. We are rarely conscious of what the specifics of those negative beliefs are. But, we know that they are there because of the disproportionate fear often felt prior to the race, and the deeply unpleasant, often overwhelming emotions that arise and linger after a tough one. Many athletes are more afraid of how they will feel emotionally after a tough race than the objective consequences of that race.

Our perspective on a race enormously influences the degree to which we believe that it means anything defining about us. Here is an idea that I have been working with lately that I hope might help with this:

It seems to me that those of us in sports – athletes, coaches, sometimes even mental performance consultants, sometimes talk about the preparation for a race like you might a drive from Philly to Boston: something that should be able to be accomplished without an issue as long as you prepare well enough. Something about which one can actually establish some expectations. There can be an emphasis on outcome goals, a focus on controllables, and great effort directed toward cultivating positive emotion. Noticing and allowing unpreferred emotions or the multitude of uncontrollable factors inherent in sport are often both consciously and unconsciously avoided.

Driving from Philly to Boston is not without its risks, but typically it is a thing most should be able to do without an issue if you focus on the right things. So often we try to see sport through this lens also, a lens which suggests a greater sense of control than is accurate.

In my opinion, a race is not like a drive from Philly to Boston. Instead, it is more like an expedition into unknown territory. For example, you don’t know what the literal weather is going to be like; If it is a cross-country race the course and conditions will vary. To varying degrees you don’t know how fit the other athletes are or what they are going to do inside the race. You don’t know how ready to give your best you will be – how fresh you feel, how focused, how excited – no matter how careful you are with your mental prep. And, you haven’t run that fast for a 5km yet so you don’t know if you can do it yet, or that today will be the day.

Also, human inner weather can be as unpredictable as outer events. Try as you might, you can’t guarantee that you will naturally be relaxed, positive and focused. Try as you might to manage your inner state, it just might be a stormy day! Over time, we can develop our physical and mental skills to give us greater control but we can never control all factors fully. As such, an athlete stepping onto the line is more like an explorer heading into the wilderness than a driver entering the interstate. I think that much pre-race stress and post-race distress arises from a runner viewing the race like the later when it would be more accurately embraced as former.

This explorer metaphor becomes more true the higher the level of racing – or the more the difficult the challenge that you take on. And, if we open our conversation beyond any one race to include a whole career, it becomes even more applicable. High level running over the long-term is wild and unpredictable. Each race is a small-scale representation of the whole thing.

To me, the differences between the mentality of the driver vs. the explorer involve their relationship with the unknown factors. For the explorer, entering a space where there are many uncontrollables, is the whole point of exploring. These are the very elements which excite explorers, which bring them alive, and which make them want to set out in the first place! Often, a certain outcome is sought and hoped for. For example, some explorers explore to learn what a land is like, or to see if they can find _________ in the jungle, or make it under their own steam from ______________to ______________, or summit ____________ mountain. But, not-knowing if they can or not is the reason they want to try.

Explorers are aware of the magnitude of the power that they are getting involved with. I understand that many explorers, and mountain climbers in particular, hold a great deal of humility and respect for the mountains that they climb, and in some cases, the spirits within those mountains. Rituals, to pay their respects and to win the favour of the land are common. Few believe adventurers believe that success is all on their shoulders. Especially not wise and experienced explorers, who have experienced their share of turning back.

Explorers also have a great deal at stake! Sometimes their lives. Given this, skilled explorers consider the task ahead as realistically and as humbly as they can. They must be honest about the hazards and their own weaknesses. They also prepare meticulously – probably more so than most athletes and certainly more thoroughly than the person driving from Philly to Boston.

I find myself wondering, what if an athlete were to take a brave look at the goals that they hope to attain, and/ or the athletic progression that they are envisioning, and honestly consider all the factors at play in determining the outcomes of those races and careers? What if athletes could find and release their attachment to the story that the outcome of any one race, or the progression of their careers should be within their control and are therefore, somehow, a measure of them? What would happen if instead, they recognized the daunting and unpredictable wilderness that is the human body, the race, and the running world? Could that be exciting? How much more free might they feel? How fast might they run?

Some years ago, mythologist and author, Joseph Campbell said: “People say that what we’re all seeking is a meaning for life. I don’t think that’s what we’re really seeking. I think that what we’re seeking is an experience of being alive.”

Later, when an interviewer asked Campbell when he had felt most alive, Campbell, who had visited countless primitive communities in wild and remote places, who had published numerous books, who had appeared on more than one TV show, and whose work was integrated greatly into the Star Wars movies, stated that the moment in his life when he had felt most alive was competing at the Penn Relays.

Such is the power and privilege of sport if we can meet it with a perspective of adventure that allows for such aliveness.

Myles, can you frame this race as an adventure that is bigger than you? It is no ultimate measure of you or your ultimate abilities. You simply get to see what you will find out there on that day – inside the race and inside yourself. Can you be as realistic as possible about how the race this likely to unfold? Ask yourself and plan ahead – where does your attention serve you best inside the race? One chunk at a time? Competing with those around you? Go out there and commit to your plan.

All of us in this tent are cheering for you! You will have to let us know if you do it!

Leave a comment